Randy Rabenold and the Bulldogs Who Went to War Part ONE

Randy Rabenold and the Bulldogs Who Went to War Part THREE

Memorial Day May 2013 Tribute to Rabenold and the Bulldogs

The Trench Art of Randy Rabenold - (Companion Post to Bulldogs Part 1)

Randy Rabenold and the Bulldogs Who Went to War Part THREE

Memorial Day May 2013 Tribute to Rabenold and the Bulldogs

The Trench Art of Randy Rabenold - (Companion Post to Bulldogs Part 1)

Part 2 of 3: Randy Rabenold and five classmates join the Marines in the peacetime of June 1948. They were known as the “Bulldogs,” an informal though closely knit group of friends from the rural west end of Lehighton. By August of 1950, Dick Carrigan, Ray “Nuny” Rabenold, Don “Duke” Blauch, William “Bill” Kuhla, Robert “Bobby” Kipp, and Randy are all fighting in Korea. All but one will return home safely.

Randy Rabenold on a warm day in Korea.

|

| Howard Manross was a member of the Brigade Band. He along with his mates played for South Korean President Sygnman Rhee in Korea at the "Bean Patch." (Photo courtesy of Tom Fortson) |

Joining in peacetime, none of the Bulldogs gave a conscious

thought to the danger their service could deliver their way. After a few short months, an unprepared U.S.

army was nearly tipping backward into the Sea of Japan pushed by the aggressor

Communist forces pressing from north of the 38th parallel.

The “First Provisional Marine Brigade” was put

together in haste in July to relieve the badgered U.S. Eighth Army. They reached Korea on 2 August. Randy lands at Pusan, the last foothold in

the south east of the peninsula. He

could hear small arms fire in the surrounding hills as he and the “infantry

went straight into combat off the gangplank.”

It wasn’t easy for the “new boots” in Korea to get

used to the mortar fire and the occasional sniper’s bullet that sent them into roadside

ditches.

One day his patrol drew the ire of a broad-chested

colonel admonishing them with, “You call yourselves Marines, get up and march!” That order was barked by the legendary Lewis

“Chesty” Puller, fast becoming a Marine Corps icon later rising to the rank of

general.

During the month of August, Randy and the rest of

the Headquarters and Service Battalion moved toward Masan and were in support

of the battle at the Naktong River. At

one point, Randy remembers traveling by rail from Pusan toward Masan on open

rail-cars.

Unknown to members of the Division, preparations were

under way for “Operation Chromite,” code name for the Inchon Landing. The Eighth Army was out of fighting room. It was only MacArthur’s logistical

masterstroke that saved the U.S. forces from complete collapse. The entire operation was pulled together,

from planning to implementation, in three weeks.

The military urgency was two-fold: With the Eighth

Army near defeat, a landing in country, across the peninsula below Seoul was

chosen not only as a way to relieve pressure the Communists were applying to

the Pusan Perimeter, but also for the element of surprise.

In early September, while Randy and the rest of the

First Provisional were holding off the communists on the perimeter, the organic

elements of the First Marine Division began arriving at Kobe Japan. By 8 September, the First Provisional began

to embark onto the ships of “Task Force 90” for the yet to be disclosed to them

mission of the Inchon landing.

Inchon Bay on the Yellow Sea has the second greatest

tidal range in the world at thirty-two feet.

(According to Randy, there are only a handful of places with a greater

range than this. The greatest one being the

Bay of Fundy near Maine.)

At best they had a brief three hour period for the

landing. There were only three dates in

which the tide would be high enough to afford the necessary depth for our

ships: 15 and 27 September and 11 October.

|

| Low tide at Inchon Bay - Inchon has one of the greatest tidal ranges in the world at 32 feet, making the amphibious assault there particularly troublesome. (Photo from Marine Corps Gazette - July 1951.) |

On 13 September, the First Provisional ceased to

exist. Its control reverted back to the First

Marine Division. Randy’s Headquarters and

Service Battalion transferred to First Division Headquarters Battalion.

Most of the Bulldogs were once again together under

the overall command of Major General Olivier P. Smith. Later, the Brigade Band would be split in

two: one staying with General Smith’s command post and the rest with divisional

commander General Edward A. Craig’s command post up at the constantly shifting

and amorphous front line.

Complicating the already tenuous plans, two typhoons

hit the area between 8 September and the launch, D-day 15 September. Bobby Kipp, Don Blauch and Tom Fortson were

part of the Division arriving from the states.

Blauch remembers how Typhoon “Jane” knocked their landing crafts over on

the beaches at Kobe while they were making preparations.

The Marines, now at sea and under the command of

Admiral Struble, loaded and launched as “Task Force 90” with 260 vessels. (Some sources use the number 290

vessels. The conflicting data is due to

the inconsistencies of sometimes counting the LSTs carried aboard the transport

ships.)

|

| Members of the First Marine Division get briefed on the assault on Wolmi-do leading to the Inchon landing. (Marine Corps Gazette, July 1951.) |

Randy’s battalion embarked from Pusan while Kipp, Blauch

and Fortson arrived from Kobe, by way of the Sea of Japan on their way to the eastern

side of the peninsula in the Yellow Sea.

Typhoon “Kesia” occurred while en-route, inflicting

more damage on our fleet and men than the enemy eventually did upon landing. The heavy rolling seas caused much

seasickness with one transport losing a few of its landing craft.

Because the size of the landing area was rather constrained and with the small three hour tide window, the ships had to be loaded

beyond their effective weight capacities which lowered their draft in the water. This caused Blauch’s LST to hang up on a

muddy sandbar.

On the first wave of men ashore and landing out too far, Blauch had to

wade ashore with over eighty pounds of gear and weapons. Much like the United Nations efforts to this

point, Blauch was literally up to his neck in water.

“The minute your legs swing over the edge and into

the cargo nets, you know you are in for it but you don’t know what its going to

be.” Seasick and nearly drowning, “was

no way to start a day of battle,” Blauch said.

These are the moments for which the U.S. Marine Corps

trains: beginning with an amphibious landing, then on to seek and destroy.

“They never expected us there,” said Blauch. He was right.

The enemy resistance was far less than they expected, allowing the

Marines to charge out ahead of their plan of attack and dangerously ahead of

their supply lines too.

Taking Kimpo Airfield was priority number one. It was sixteen road miles inland and was

secured within fifty hours of the landing while elements of the Division were

advancing to the Han River and onto Seoul.

Randy was among the “second wave” on 16 September, mainly facilitating at the supply dumps and

setting up General Smith’s subsequent command posts as they advanced toward

Kimpo. They were told they could expect

to get killed, as the enemy was known to be dug in there and at least at one

point, they did take a lot of enemy mortar and tank fire at the command post.

He remembers first landing on the island of

Wolmi-do, a Korean resort island that guarded the entrance to the bay at Inchon. Upon landing, the only enemy encounter he

remembers seeing were “about fifty North Korean’s held under the gun” of his

fellow Marines in a drained-out swimming pool.

Meanwhile, ANGLICO Don Blauch was forward calling in

air-strikes to the carriers on enemy movements and positions. He picked

landmarks out for the pilots to guide them into their coordinates.

|

| Don "Duke" Blauch's radio communications certificate. As a forward observer, Blauch was routinely ahead and in the line of enemy fire. |

Much to their chagrin and disturbing their peace of mind, the pilots periodically had to trade the relative safety of the air to rotate to the

ground to serve alongside the forward air observers like

Blauch. As a result, Blauch developed a

few close friendships that would pay dividends later.

Sometimes the enemy used fugitives and children as

shields to the entrances of their caves and bunkers.

Blauch spoke from a place of necessity devoid of bravado when he said, “When it’s your butt or theirs on the line, you

take out their butt.” (Obviously Blanch didn’t

use the word “butt.”)

By 20 September, General MacArthur and South Korean

President Sygnman Rhee celebrated outside Seoul. This was near the time when MacArthur

prematurely predicted we’d be home by Christmas. One day around this time Rabenold distinctly

remembers MacArthur rolling by, replete with his corn-cob pipe, aviator glasses

and all.

On 21 September 1950, Bulldog Robert “Bobby” Kipp, part

of Second Battalion/First Division’s FOX Company lead position, had two enemy

tanks and a supply truck pass within the bounds of their position. Official reports state they were under

friendly fire for about two hours from the left and heavy artillery and mortar

fire from enemy on the right.

At about 1830 (6:30 PM) FOX was joined by DOG and

EASY companies for the night. The enemy,

entrenched on the high ground, caused the Marines to dig a defensive perimeter in and along the

road. They were north of the Han River

along Kalchon Creek.

Kipp and his foxhole mate began digging, perhaps just a bit deeper than normal, prompted by the daytime firefight. It is not known when the radio jeep pulled in

next to their foxhole that night. But

the engine was let running all night filling Kipp’s trench with carbon

monoxide. Kipp was found unconscious. His foxhole-mate survived. Blauch later learned of his friend’s fate

from members of Kipp’s platoon.

|

| Kipp's front page KIA article in the Lehighton Evening Leader from 4 October 1950. Official military reports list the day of his death as 21 September. Interesting if true that his parents last heard from him on the 21st. Even though they were driving the enemy north, one would assume perhaps he had time enough to jot one last letter. Don Duke Blauch was the last Bulldog to speak with Kipp while embarking across the Pacific that August (see Part 1). The contents the letter on the same day he died would be of interest. |

Randy remembers visiting the Kipps as soon as he returned home, their grief untouchable. He recalls them with a forgotten fondness, saying that Mrs. Kipp was the nicest woman he’d ever known.

|

| Robert Kipp lies beside his parents at Lehighton Cemetery near the northeast corner near Iron Street. |

|

| Bobby Kipp all smiles the Fall before his death. Kipp died September 21, 1951, not quite twenty years old. |

With the enemy on the run and Seoul reclaimed by 27

September, half of the First Battalion/First Division made a landing on the

east side of the peninsula in the Sea of Japan at Wosan. From there, they moved on up to Hungnam.

Half of those continued to push the communists

toward the Yalu River, the Chosin Reservoir and the border with China,

movements that would soon entice the Chinese to enter in full force. They cited their own national security for

their actions, since the reservoirs of North Korea were part of their

electrical power grid.

Randy Rabenold and his half of the battalion

remained to the rear with General Smith’s command post near Kimpo airfield, “a

dreary place surrounded by rice paddies.”

Sometime after the dust settled after the Inchon Invasion and before the action at Chosin Reservoir, the Brigade Band played perhaps for the only time while in Korea.

It was at the "Bean Patch," General Craig's command post, where the Brigade received South Korea's President Sygnman Rhee for a head of state visit.

The 'Bean Patch' was also the location of General Smith's memorable bonfire after the Chosin Reservoir. Having continuously worn the same clothing from the non-stop fighting from October through December, the Marines were issued complete new sets of clothing and were ordered to burn their old ones to prevent scurvy.

It was at the "Bean Patch," General Craig's command post, where the Brigade received South Korea's President Sygnman Rhee for a head of state visit.

The 'Bean Patch' was also the location of General Smith's memorable bonfire after the Chosin Reservoir. Having continuously worn the same clothing from the non-stop fighting from October through December, the Marines were issued complete new sets of clothing and were ordered to burn their old ones to prevent scurvy.

|

| The Bean Patch, General Craig's Command Post - President Rhee stands with arms folded next to saluting General Craig. It is the only time the band played as a unit while in Korea. (Fortson.) |

It is here, probably sometime near the end of

September or the beginning of October, that Randy learns his father Zach had died

on the 26th of August. He is

given leave and flies out of Kimpo on a two-engine propeller plane. Though it could’ve held up to thirty people, it was just Randy, one other GI and the flight crew.

They made a fuel stop at Midway Island and

He took a Greyhound Bus, taking a four-day cross-country

trip through Utah, Colorado, Missouri and Ohio.

Though thirty-days were considered a standard leave for family

bereavement, once home, many WWII vets told Randy “they probably won’t ship you

back.” “And besides,” they said,

“MacArthur promised you’d be home by Christmas.”

|

| Randy Rabenold's dad Zach died 26 August 1950. |

Then came the telegram ordering him to report back

to Camp Pendleton for re-deployment. In

the time he was gone, the slaughter of what became known as the “Frozen Chosin”

had begun. Over 100,000 determined Chinese

who seemed impervious to the sub-twenty-below zero temperatures, came across

the Yalu River in force.

Despite having a superior line of supply, seemingly

endless munitions, heavy artillery and dominate air power support, the U.S.

struggled against these relatively spartan Chinese soldiers in canvas shoes and

jackets.

The cold caused a myriad of problems for our

servicemen. Carbines were freezing,

grenades wouldn’t detonate, mortar tubes couldn’t be re-positioned due to

freezing to the ground, and support from the howitzers back at

Hagaru-ri grossly under-fired due to the cold, raking friendly fire over our

own surprised men.

The standard issue gun oil froze the carbines and

the BARs. GI’s found the captured whale

oil used by the Chinese helped as well as urinating on their barrels to keep

the carbon from seizing their muzzles.

This being easier said than done under steady sniper fire.

C-rations froze solid. The only way to keep some of your corned beef

in near edible form was to keep a can under each armpit. Otherwise, most men could only eat the hard

candy in their packs, though eating the “Charms” was considered unlucky by the

Marines since WWII.

Frostbite was the biggest casualty culprit. To throw a grenade, one needed to take off

his bulky gloves. But skin instantly froze

to the metal, tearing off sheets of flesh.

The Marines developed the tactic of “warming tents,”

using 16-by-16 foot tents with a camp stove, set up within the bounds of their defensive

perimeters. Men could rotate through them when possible. According to Blauch though, “You

could fill up your canteen with piping hot coffee and it would be frozen solid

by the time you returned to your foxhole.”

The Navy corpsmen (or Medics in Army parlance) were

held in the highest regard by every Marine.

You may hear a Marine complain about everything from their grub to their

commanders, but you will be hard pressed to ever hear a Marine disparage these

men of staggering bravery. Sentiments

echoed by Fortson, Blauch and Rabenold.

They constantly carried morphine syrettes in their

mouths to keep a ready supply thawed.

They had to deal with plasma bags freezing solid and the Catch-22 of cutting

open the clothing of the wounded to treat a wound versus exposing the injured

flesh to frost bite.

But there were a few benefits to the cold: non-arterial

wounds nearly instantly congealed saving many from bleeding to death. And by the end of November, with so many dead

encircling the trapped forward elements of the Division, the bodies did not

smell of death.

The Chinese were masters at winning the battle of

the mind. On 29 November at precisely

2200 hours (10 PM), a Chinese officer on FOX Hill near the Reservoir began an

oratory over a loud speaker meant to dishearten our men, encouraging them to

save themselves from the impeding slaughter by surrendering.

Then Bing Crosby blared “White Christmas” followed

by a Chinese accented English song with the refrain, “Marines, tonight you

die.” Over the lower side of the hill,

behind the Chinese line, they lit a large fire to illuminate the skyline which allowed

our men to see the thongs of white quilt-coated Chinese servicemen, about to

mount their evening assault, silhouetted against the dark sky.

In the short month of November and into December, the

Chinese learned to attack at night, using their advantages of stealth and

overwhelming numbers to overcome the advantages of the Marines. Our high command had underestimated them, the

harden veterans of their five-year war against the Chinese Nationals.

They seemed to be everywhere, particularly at night. They also employed the cunning tactic of laying among the dead all day long, lulling unsuspected G.I.s to their deaths. Many a Marine witnessed "walking dead," hitherto fore "dead" soldiers getting up just in time to join their comrades for their routine evening assault.

They seemed to be everywhere, particularly at night. They also employed the cunning tactic of laying among the dead all day long, lulling unsuspected G.I.s to their deaths. Many a Marine witnessed "walking dead," hitherto fore "dead" soldiers getting up just in time to join their comrades for their routine evening assault.

Our average G.I. soon took them seriously. Word quickly spread that men had being

bayoneted in their sleep. Prompting many, despite the subzero temperatures, to sleep in their open foxholes with unzipped sleeping bags.

Their primitive bugle calls, drums and trumpets announcing their charges were particularly disheartening.

The Marines were caught in a surreal paradox: They

were an amphibious force accustomed to fighting on beaches but now battled over

solid, frozen, desolate earth.

|

| John J Murphy and Gene Holland in May 1950 - Gussy-up Hollands car as part of getting ready for leave. The Korean Conflict was far off the RADAR then. |

It was under these extreme conditions that division

band mate "Gene" Holland was killed with several others wounded at this place

forever known as the “Frozen Chosin.”

The men who fought there too would forever be known as the “Frozen Chosen”

or “Chosen Few.”

PFC Francis Eugene "Gene" Holland was part Cherokee American Indian and a bandmate of Rabenold and Fortson. His friend Robert Wood said of him, "for the band he played trumpet but for the Marines" at Koto-ri, on the main supply road near Chosin, "he played light machine gun."

Dick Sharp said, "Gene and I trained as stretcher bearers, but upon our arrival in Japan, our MOS was changed to "0331," .30-cal machine guns. Gene was on my gun the night of December 6th or early on the 7th. It took me a long time to get over his death. I still correspond with his sister. A wonderful family and I still miss him. I got to visit his grave in California and it helped me to heal. I named my only son after him, Gene Holland Sharp."

He was reported killed on December 7th, 1950. He was the only bandsman, of anyone's knowledge, to have died in Korea.

Rabenold explained that gunners sometimes rotated with their ammo feeder and ammo carriers. Explaining Sharp's (Nicknamed "Not-so," as in "Not So Sharp" as he was affectionately chided by his band mates.) extra burden for his friend who died while on duty with his gun. Rabenold said there were times when he filled in on the gun while stationed at various outposts in Korea. In an attempt to draw expose enemy snipers, they would get orders to fire toward the approximate enemy positions in the hope they would return fire for spotters to pinpoint their nests.

PFC Francis Eugene "Gene" Holland was part Cherokee American Indian and a bandmate of Rabenold and Fortson. His friend Robert Wood said of him, "for the band he played trumpet but for the Marines" at Koto-ri, on the main supply road near Chosin, "he played light machine gun."

|

| Gene Holland at Camp Pendleton in July 1950 outside the Band Barracks just before shipping out. Holland was a native of Eagle Rock, CA, a suburb of Los Angeles. |

Dick Sharp said, "Gene and I trained as stretcher bearers, but upon our arrival in Japan, our MOS was changed to "0331," .30-cal machine guns. Gene was on my gun the night of December 6th or early on the 7th. It took me a long time to get over his death. I still correspond with his sister. A wonderful family and I still miss him. I got to visit his grave in California and it helped me to heal. I named my only son after him, Gene Holland Sharp."

He was reported killed on December 7th, 1950. He was the only bandsman, of anyone's knowledge, to have died in Korea.

Rabenold explained that gunners sometimes rotated with their ammo feeder and ammo carriers. Explaining Sharp's (Nicknamed "Not-so," as in "Not So Sharp" as he was affectionately chided by his band mates.) extra burden for his friend who died while on duty with his gun. Rabenold said there were times when he filled in on the gun while stationed at various outposts in Korea. In an attempt to draw expose enemy snipers, they would get orders to fire toward the approximate enemy positions in the hope they would return fire for spotters to pinpoint their nests.

Rabenold went back to Japan and was assigned to a

casual company of “bakers, cooks and bandsmen.”

They were halfway across the Sea of Japan (“..the deepest sea in the

world,” he adds) with an M-1, two

bandoleers and a cartridge belt of ammo, a “field transport pack” which

contained spare clothes (underwear etc.) and their ever constant companion entrenching tool.

They were first told they had to go in and save the

division trapped at the reservoir. Word

spread among the men at the front that relief was coming, some finding it humorous

that a casual company of cooks and bandsman would be able to save them.

Halfway across, their orders changed and they landed

at Hungnam (though Randy remembers it first as Hagaru-ri; and later thought

Hangnum; Hagaru-ri is a land-locked village just south of the Chosin Reservoir,

north of Koto-ri. See the two previous maps.)

They learned, though completely surrounded and

outnumbered, that the division was able to fight its way out. On December 19th, much of the

Marine Division was evacuated from Hangnum.

Fortson, Rabenold, Nuny and the rest of the Division embarked to

Pusan.

Randy said the men were shattered, saucer-eyed with

battle fatigue and thousand yard stares.

It was Christmas time and they were ordered to stop talking of the

possibility of going home as MacArthur promised.

|

| Some R & R In Kobe Japan - August 1951 Tom Fortson (right) has a drink with Jim Chambers and Steve Cain. |

Fortson recalls enjoying the respite from the front,

being with Dick Sharp in Masan on Christmas Eve as they both celebrated their

twenty-first birthdays so far away from home.

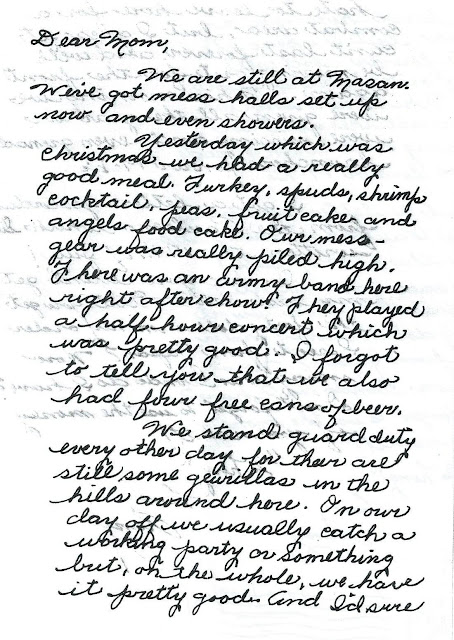

The transcript of Randy’s letter home, in impeccable

handwriting:

Christmas 1950 – Masan, Korea

Cpl

R Rabenod 1071112

HQ

Co.; HQ Battalion

First

Marine Division

“Dear

Mom,

We

are still at Masan. We’ve got mess halls

set up now and even showers.

Yesterday

which was Christmas we had a really good meal.

Turkey, spuds, shrimp cocktail, peas, fruit cake and angels food

cake. Our mess-gear was really piled

high. There was an army band here right

after chow. They played a half hour

concert which was pretty good. I forgot

to tell you that we also had four free cans of beer.

We

stand guard duty every other day for there are still some guerillas in the

hills around here. On our day off we

usually catch a working party or something but, on the whole, we have it pretty

good. And I’d sure hate to leave here

for a combat area, but I guess it can’t last forever and we’ll be moving out

for the front again. This morning we

were given all the gear we were missing and even grenade launchers for our

M-1’s.

I

got a letter yesterday from the Paulsens which was written the 17th

of July!

In

case you didn’t get my last letter. Did

you get the forty dollar money order I sent from Japan? How many war bonds do I have? Don’t forget to use the money if you need it!

“so long”

Love, Rany

“Dear

Mom,

Randy’s captioned “so long” above was a homage to his

mother Mary Rabenold’s familiar yet staid farewell, a phrase she used the whole

of her 93-year life. But more so than

ever, with the distance, the homesick mourning, and the unpleasantness of a

bitter, painful struggle against a seemingly unrelenting enemy, those two

words, more than any, seemed to capture the essence of that moment.

Even though he was far from home, Randy felt lucky

to be alive. And though he missed his fallen

buddies, especially Bobby Kipp and his Dad, he began to see the silver-lining

of his father’s death, and how it may have saved his life.

|

| Mary and Zach Rabenold c 1930. |

|

| Perhaps the last picture of Zach, taken by neighbor Johnny Nothstein in 1947. Zach's death sent Randy home on bereavement leave while the Division was trapped at the Chosin Reservoir. |

Sources:

- Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and

Breakout in Korea. Texas: Texas A &

M Press, 1987.

- Drury, Bob and Clavin, Tom. The Last Stand of FOX Company. New York: Grove Press, 2009.

- Hastings, Max.

The Korean War. New York: Simon

& Schuster, 1987.

- Interviews and letters of Donald Blauch, Tom

Fortson, Wally Norsworthy, and Randy Rabenold, 2012-2013.

- Korean War Project.

1st Provisional Marine Brigade De-classified Special Action Report,

2 August to 6 September, 1950.

- Korean War Project.

1st Provisional Marine Brigade De-classified Special Action

Report, September to October, 1950.

- Marine Corps Gazette, July 1951.

- Speights, R. J. Roster of the 1st

Provisional Marine Brigade, Reinforced for August and September While in Action

in Korea. Austin Texas, 1990.

"So Long" - Mary's preferred goodbye.

She lived a long time, 33 years, as a

widow after Zach's death in 1950.

She lived a long time, 33 years, as a

widow after Zach's death in 1950.